Center for Communications, Health and the Environment

Immediate Action Required:

Understanding the Tobacco Epidemic and Stopping It in Its Tracks

by Dr. Judith Mackay, Director, Asian Consultancy on Tobacco Control, Kowloon, Hong Kong, and Director of Global Tobacco Control Programmes, and Project Coordinator, Bloomberg Initiative to Reduce Tobacco Use, World Lung Foundation

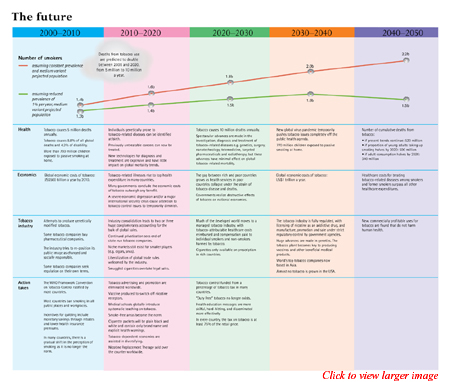

Within 150 years of Columbus finding “strange leaves” in the New World, tobacco had made its way across the globe. More than 500 years later, at the beginning of the 21st century, about one-third of adults throughout the world used tobacco. Today, “tobacco...is responsible for about 5 million deaths worldwide every year,” laments Dr. John R. Seffrin, chief executive officer of the American Cancer Society. And if current trends continue through 2025, it will kill 10 million individuals globally each and every year, with 7 million of these deaths occurring in the developing world.

Tobacco is the globe’s biggest killer. No other consumer product is as dangerous, or kills as many people. It led to the deaths of 100 million smokers in the 20th century, and, if left unchecked, 10 times as many – more than 1 billion people – are estimated to die from tobacco use in the 21st century. In fact, tobacco will eventually kill about 650 million smokers alive today. That’s about 10 percent of the current total global population!

Smoking and Gender

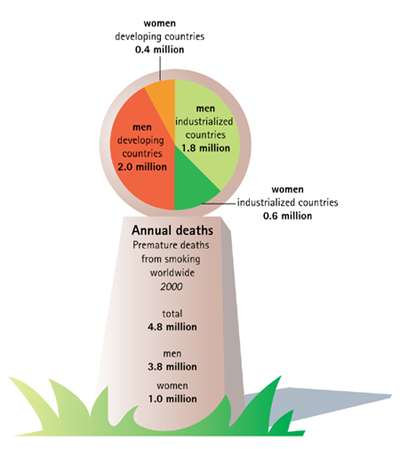

Cigarettes kill 50 percent of all lifetime users. Half die in middle age, between 35 and 69 years old, with one person dying every 10 seconds due to smoking-related diseases. Yet, smoking has been, and in many countries continues to be, portrayed by its sellers as a mainly masculine habit, linked to health, happiness, fitness, wealth, power and sexual success.

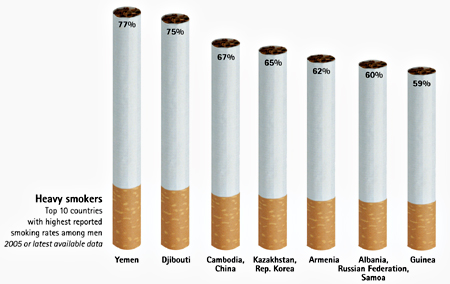

Almost 1 billion men in the world smoke – about 35 percent of men in developed countries and 50 percent of men in developing countries. Comprising more than 300 million male smokers – more than the entire U.S. population – the Chinese market is “the most important feature on the landscape,” according to global tobacco company Philip Morris. It is also a clear sign of the enormity of the problem. In fact, 60 percent or more of males in China and the Russian Federation smoke, and in Yemen and Djibouti, percentages stand at 77 and 75, respectively, engendering sickness, premature death and sexual problems at an alarming rate.

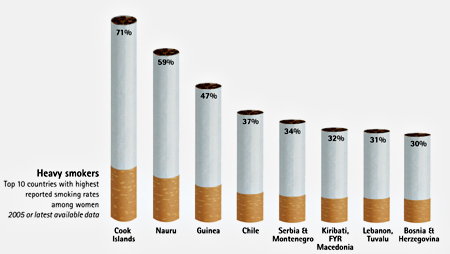

But men aren’t the only ones lighting up – and dying by the millions. About 250 million women in the world are daily smokers, with about 22 percent of women in developed countries and 9 percent of women in developing countries smoking tobacco. (In addition, many women in South Asia chew tobacco.) Overall, 11 percent of women worldwide smoke tobacco, with female smoking rates in the Cook Islands and Nauru at 71 and 59 percent, respectively, and rates in Guinea approaching 50 percent.

Not unlike its marketing tack with males, the tobacco industry promotes cigarettes to women using seductive, but false, images of vitality, slimness, emancipation, sophistication and sexual allure. And tobacco companies produce a range of brands specifically targeting women. Most notable are the “women-only” brands, “feminized” cigarettes that are long, extra-slim, low-tar, light-colored or mentholated.

Trends and Consumption Realities

Although the news surrounding tobacco is overwhelmingly bad, trends in both developed and developing countries show that male smoking rates have peaked and, slowly but surely, are declining. This is an extremely slow trend over decades, however; in the meantime, tobacco is killing nearly 4 million men every year. In general, the higher-educated man is giving up the habit first, so that smoking is increasingly becoming a habit of poorer, less educated males.

Cigarette smoking among women is also declining in many developed countries, notably Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. But this trend is not found in all developed countries. In several southern, central and eastern European nations, cigarette smoking is either still increasing among women or has not shown any measurable decline.

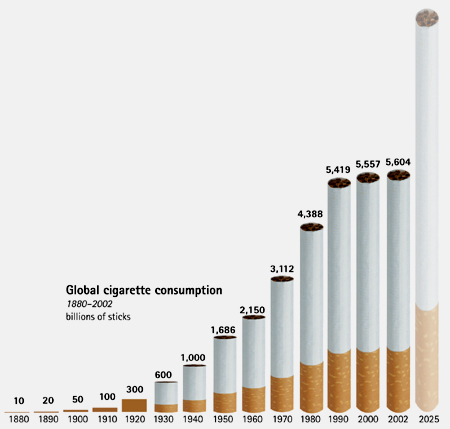

Global consumption of cigarettes has been rising steadily since the end of the 19th century, when manufactured cigarettes were first introduced. While consumption is leveling off and even decreasing in some countries, more people are smoking, and each smoker is consuming a greater number of cigarettes. In fact, more than 10 million cigarettes are smoked every minute of every day around the world, and if current trends continue, smokers will consume 9 trillion cigarettes annually by 2025!

Meanwhile, the number of smokers will expand, mainly due to population growth. By 2030, there will be at least another 2 billion people in the world. Unless smoking prevalence rates decline dramatically, the absolute number of smokers will increase. And the expected continuing decrease in male smoking prevalence may be offset, in part, by an increase in female smoking rates, especially in developing countries.

The consumption of tobacco has already reached the proportions of a global pandemic. Tobacco companies are cranking out cigarettes at the rate of 5.6 trillion a year – nearly 900 cigarettes for every man, woman and child on the planet. In China alone, cigarette production increased by 700 percent between 1980 and 2003, from 225 billion cigarettes per year to a staggering 1.8 trillion – 97 percent of which are consumed in-country.

Except for chewing tobacco in India and possibly kreteks in Indonesia, cigarettes are the most common method of consuming tobacco throughout the world, accounting for the largest share of manufactured tobacco products, 96 percent of total value sales. At 56 percent, Asia and Australasia comprise the largest share of global cigarette sales, followed by Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Economies (13%), the Americas (12%), Western Europe (10%), and Africa and the Middle East (8%).

The top five cigarette-consuming countries are China, the United States, the Russian Federation, Japan and Indonesia. China accounts for about one-third of all cigarettes smoked worldwide, an astounding 1.75 trillion a year. This is more than three times the 402 billion consumed in the United States, the second largest cigarette consumer in the world. In 2003, China National Tobacco Corporation, China’s state-run tobacco monopoly, had the greatest share of the global cigarette market at 33.7 percent; well-known giants Altria/Philip Morris and British American Tobacco (BAT) captured only 17.6 and 15.1 percent, respectively.

Health Risks

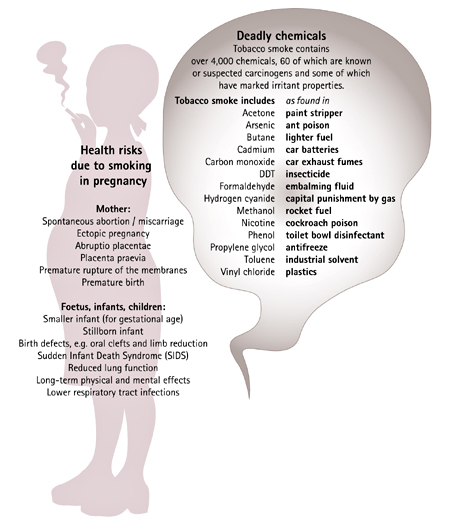

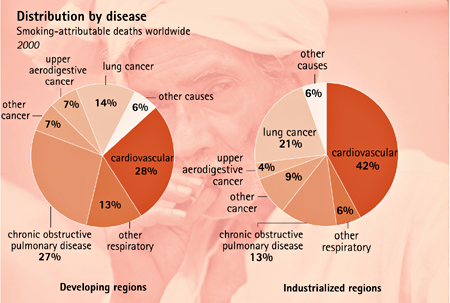

Tobacco is packed with harmful and addictive chemicals. Scientific evidence has shown conclusively that all forms of tobacco cause health problems and significantly increase the risk of death or disability. Smokers have markedly increased risks of multiple cancers, particularly lung cancer, and are at far greater risk of heart disease, strokes, emphysema, and many other fatal and non-fatal diseases. Accounting for more than 6 percent of total health care expenses in the United States in 1999, smoking is responsible for 90 percent of all lung cancer worldwide, 75 percent of chronic bronchitis and emphysema, and 25 percent of cases of ischemic heart disease. In fact, every cigarette takes seven minutes off a smoker’s life!

Women suffer additional health risks. Smoking in pregnancy is dangerous to the mother as well as to the fetus, especially in poor countries where health facilities are inadequate. Maternal smoking is not only harmful during pregnancy, but also has long-term effects on the baby after birth. This is often compounded by exposure to second-hand smoke (SHS) from the mother, father or other adults smoking. The risk of lung cancer in non-smokers exposed to SHS is increased by between 20 and 30 percent, and the excess risk of heart disease is 25 percent. Adverse health effects experienced by exposed children – and almost 50 percent of children worldwide are exposed to tobacco smoke – include respiratory infections such as pneumonia and bronchitis, asthma induction or exacerbation, middle-ear infections and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS).

While tobacco undoubtedly kills millions more than it helps, nicotine is currently used as an insecticide, and researchers continue to seek other uses for the tobacco plant, such as genetic engineering. There has also been action into examining other uses of land that currently grows tobacco.

Marketing Madness and the Politics of Promotion

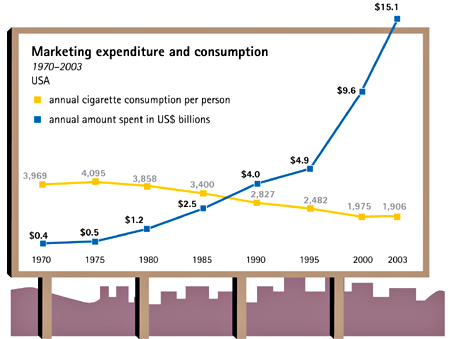

Meanwhile, cigarettes – the tobacco user’s weapon of choice – are possibly the most marketed product in the world. While there is no reliable estimate of global cigarette marketing expenditures, clearly, tens of billions of U.S. dollars are used for this purpose every year. In America alone, more than $15 billion is spent annually on marketing cigarettes – the equivalent of more than $270 per smoker, 65 cents per pack, and $1.7 million every hour of every day! This amount is especially astronomical given that tobacco advertising is prohibited on U.S. television and radio, certain types of outdoor advertising and sponsorship are limited, and cigarette sales are falling. Price discounts (payments made to retailers to reduce the price of cigarettes to consumers) account for two-thirds of the total marketing expenditure. Unfortunately, such excessive marketing appears to be paying off – for the tobacco companies, that is. In the United States, the average smoker spends $1,600 per year on cigarettes, and in Vietnam, smokers spend 3.6 times more on tobacco than on education, 2.5 times more on tobacco than on clothes, and 1.9 times more on tobacco than on health care.

Cigarette marketing is particularly bold and aggressive in developing countries. Cigarette advertising on television and radio is common, and a variety of other venues are exploited, including sports, arts, music, fashion and the Internet, which offers the advantage of a virtual, and seemingly unregulated, tobacco shop. Throughout both the developed and the developing world, underhanded advertising techniques are employed, such as the strategic placement of cigarette brands and cigarette smoking in films, which is not recognized, and regulated, as advertisement.

In addition to the billions allocated to advertising, tobacco companies donate a small percentage of their profits to civic, educational and charitable organizations to enhance their public image. The tobacco industry also spends tens of millions of dollars to influence public policy. Tobacco companies make major cash contributions to elected officials and political parties, subsidize air travel, finance political conventions and inaugurations, and host fundraisers for politicians. From 1994 to 2004, for example, U.S. tobacco companies donated more than $26 million in political contributions to U.S. federal candidates, political parties and committees.

Comprehensive tobacco legislation was defeated in the U.S. Senate in 1998. Those who voted against the legislation had received, on average, nearly four times as much money from the tobacco industry in the two years before their last election than those who voted in favor of the bill. Buying influence and favors through political contributions is common practice; however, most countries do not require mandatory reporting of tobacco industry inducements.

In addition to making contributions, tobacco companies conduct direct lobbying and sophisticated public relations campaigns, using paid media to influence the opinions of political decision-makers. For instance, the tobacco industry spent nearly $10.4 million to lobby the U.S. Congress in the first six months of 2004, which amounts to about $122,000 for every day Congress was in session. The previous year, in 2003, U.S. tobacco companies spent $21.8 million on lobbying, with Altria/Philip Morris shelling out 62 percent of that, or $13.5 million. Emphasizing Big Tobacco’s “international” approach to marketing, Philip Morris’ own documents expressed that in 1987 the company and the industry were “positively impacting the government decisions of Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE through the creative use of market-specific studies, position papers, well-briefed distributors who lobby, media owners and consultants.”

Reducing Smoking and Tobacco-Related Disease and Death

Reducing tobacco use requires knowing what works, and applying this information systematically. In developed countries, there has been no shortage of reliable data on tobacco use, thanks in part to investments by international development agencies and foundations. Tobacco-control research in the developing world is also beginning to flourish; however, barriers continue to exist, with insufficient investments in research infrastructure resulting in the lack of standardized data on tobacco consumption, weak communications networks and a shortage of health research professionals.

The source of the funding for tobacco-control research is of equal importance. Historically, tobacco companies have sponsored research, promising complete independence, only to suppress unfavorable findings. Meanwhile, an analysis of National Institutes of Health spending on research funding for major health problems in 2003 revealed that only US$1,200 per related death was spent on tobacco use, compared with $10,000 on cancer, $62,500 on asthma and $200,500 on HIV/AIDS, even though tobacco is the globe’s number-one killer.

Fortunately, the tobacco-control network is committed and far-reaching, with national capacity-building at the top of its agenda. The Framework Convention Alliance (FCA), an umbrella organization of 200 tobacco-control organizations, contributes significantly on this front in 80 countries by organizing workshops and providing technical expertise in support of ratification and implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the world's first public health treaty and the centerpiece of WHO’s Tobacco Free Initiative (TFI). Also playing an important role is GLOBALink, an international, Internet-based network of tobacco-control advocates who continuously share their knowledge and experience on a broad range of public health, medical, legal, technical, social and cultural issues related to tobacco control. Several other international and regional organizations also work exclusively on tobacco issues, including the International Non Governmental Coalition Against Tobacco (INGCAT), the International Network of Women Against Tobacco (INWAT), the Asia Pacific Association for the Control of Tobacco (APACT), and the European Medical Association on Smoking or Health (EMASH). In addition, there are two dedicated international journals on tobacco: Tobacco Control and the Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco.

Legislation also plays an active role in tobacco control. Encouraged and supported by the FCTC, smoking bans in public places, for example, protect the health of non-smokers as well as smokers, while limiting cigarette use in general. Today, most airlines are smoke-free, and the global trend is towards a safer, cleaner indoor environment in the home, public venues and workplaces. Smoking bans are economically beneficial to employers, leading to a reduction in accidental fires, lower insurance premiums and reduced employee absenteeism. And while the tobacco industry may claim financial hardship due to bans in places such as restaurants, the facts may indicate the opposite. For instance, when California banned smoking in restaurants and bars serving food and alcohol in 1996 and 1998, respectively, the state has seen sales rise in these venues through 2004.

As governments recognize the scourge of tobacco and the need to discourage its use, restrictions and outright bans on tobacco advertising are becoming common. Evidence suggests that comprehensive bans on all forms of tobacco promotion are effective in reducing smoking rates by more than 6 percent per year, while partial restrictions have limited or no effect.

Cigarette packaging becomes more important as advertising restrictions are implemented; it becomes the primary avenue through which companies establish brand imagery and compete for potential customers. Thus, many countries advocate plain packaging. In accordance with the FCTC, some also propose to ban words such as “Light” or “Mild” that may imply that the cigarettes contain fewer dangerous constituents.

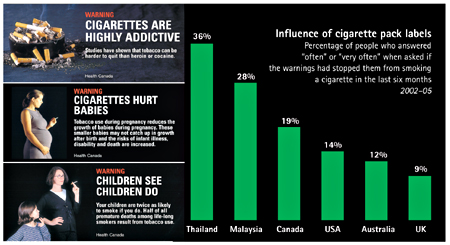

Reports from Canada and Australia suggest that plain packaging may increase both prominence and believability of health warnings, which were introduced in the 1960’s following scientific reports on the hazards of smoking in the United States and the United Kingdom. The early warnings were weak and inconspicuous, but contemporary Canadian warnings cover 30 percent or more of a pack and are among the most vivid in the world – so graphic, in fact, that when they debuted in 2002, 90 percent of smokers noticed them, and 44 percent felt an increased motivation to quit, 43 percent were more concerned with the health effects of smoking and 21 percent actually resisted the temptation to smoke on one occasion or more after seeing them.

Canada is not the only country to fight back. Cigarette packs in Brazil also display graphic images, along with a phone number to a support center for smokers wishing to quit. Australia’s packs include cessation tips. And the majority of countries in Western Europe and the European Union require health warnings to cover 30 percent or more of a pack. As of the end of 2007, 16 countries across the globe required graphic packet warnings. Bhutan has even gone so far as to ban tobacco sales completely, making health warnings unnecessary.

In addition to information, education – and the public understanding, support and demand that comes with it – is essential for sustained progress in tobacco control. Schools are an ideal venue to teach about the harm from smoking, to provide students with refusal skills and to change beliefs, attitudes and intentions. A school tobacco-control program must prohibit tobacco use at all school facilities and events, help students and staff to quit smoking, and ideally make the course part of a coordinated school health program, reinforced by community-wide efforts.

Smoking cessation is an important component of tobacco-control, since the major health risks decrease when smokers quit, even in those who have smoked for 30 or more years. As for incentives to influence quitting, a 10 percent price increase reduces consumption by about 4 percent in high-income countries and 8 percent in low- and middle-income nations. A 10 percent tax increase in cigarette price in China alone would save between 1.4 and 2.2 million lives!

While most smokers quit on their own, availability of support and treatment, including clinics, quitlines, Internet sites, skills training, nicotine replacement therapy and other pharmaceutical treatments, can help. Anti-tobacco campaigns also play a part in smoking cessation. Organized every second year by the National Public Health Institute of Finland and supported by WHO, the international Quit & Win campaign reports that 15 to 25 percent of its participants are still not smoking after one year. In 2004, 700,000 people participated in the campaign worldwide, with 105,000 to 175,000 smokers kicking the habit by 2005 as a result.

While anti-tobacco programs help, the price of tobacco is the single largest factor influencing short-term consumption patterns. More importantly, price is critical in determining how many young people will start smoking, and it profoundly influences long-term consumption trends as well. In short, smoking goes down as prices go up, and youth, minorities and low-income smokers are two to three times more likely than other smokers to quit or smoke less in response to price increases.

Litigation, however, may be the proverbial “nail in the coffin” of the tobacco industry. It has put the industry on the defensive, forced tobacco companies to the bargaining table, and resulted in some large settlements, with the industry paying U.S. states billions of dollars a year. Spending $933 million in legal costs between 2002 and 2004, in 2005, Philip Morris International and its affiliates had 302 lawsuits pending against the group. The previous year, BAT faced 14 tobacco-related class action lawsuits in the United States alone. Outside America, tobacco litigation is a new phenomenon; however, some recent cases show the potential for litigation to advance tobacco control. Australia has seen major rulings on passive smoking, and public interest litigation is rising in France, India, Niger and Uganda.

It is now well-established that tobacco-control measures can lead to a reduction in smoking, and WHO, the World Bank and tobacco-control advocates have identified a combination of the following as having a measurable and sustained impact on curtailing tobacco use:

• increased excise taxes

• controls on smoking in public places and workplaces

• bans on tobacco advertising, sponsorship and marketing

• graphic, rotating and explicit warnings on cigarette packs

• tough counter-advertising and health education

• expanded access to effective means of quitting

• litigation

• tight controls on smuggling.

Endgame

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times…”

This famous line from Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities refers to the French Revolution, but it is equally applicable to today’s tobacco epidemic, which, despite greater understanding and more resources than ever targeting it, is predicted – by the tobacco industry itself – to experience a global expansion in the next few years. The increases in cigarette consumption lie principally in developing nations and the emerging markets of Asia, Africa and Latin America, while consumption in industrialized countries will likely remain static or decline.

More than a decade ago, WHO predicted that the differential in wealth between rich and poor countries would widen as a result of tobacco, leading to compromise in sustainable development. This transfer of the tobacco epidemic from rich to poor countries, with its health and economic consequences, is one that developing countries – and the world – can ill afford.

While future projections are necessarily speculative, it is safe to say that, as we enter 2008, the future looks bleak. The global tobacco epidemic is worse today than it was 50 years ago, and it will be even worse in another 50 years unless an extraordinary effort is made – now.

Several countries, including many western countries, Singapore, Thailand, Japan and Hong Kong, have already shown that smoking rates can be reduced. These successes can be reproduced by any responsible nation, but only through immediate, determined and sustained governmental and community action.

Even if we assume a reduced prevalence of 1 percent and a medium variant in the projected population, the world is still looking at 1.5 billion smokers in 2050. The future epidemic depends on understanding the issues, and it is inextricably tied to today’s policies, politics and actions.

“If we were able to cut adult cigarette consumption by just 50 percent worldwide, we could avert more than 300 million needless deaths within the next 50 years,” explains Seffrin.

And so we stand at a crossroads with the future in our hands. The key is action – robust and enduring measures to protect the health and wealth of nations, and of the world. Countries like Canada, Australia and Brazil have already gotten smokers to take notice of health warnings, and international initiatives such as World No Tobacco Day are securing cessation while communicating the hazards of smoking and serving as an opportunity for public advocacy against lighting up. Meanwhile, TFI aims to reverse the worsening trends in health caused by tobacco and to add momentum to a critical public health struggle by building partnerships for action against tobacco, commissioning policy research to fill gaps, and accelerating national and global policy to implement strategies. And WHO’s FCTC now has more than 150 nations working to apply constitutional restrictions on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship within their respective countries. Already the treaty has mobilized resources, rallied hundreds of NGOs, encouraged government action and led to the political maturation of health ministries across the globe.

We have the ability to extinguish untimely disease and death from tobacco use. Doing so calls for an upsurge of local, national and global action against tobacco and its damaging effects. Momentum is building, and as it does, the world is beginning to see the light, instead of asking for one.

This article is based on excerpts and facts from The Tobacco Atlas, Second Edition, a 2006 publication of the American Cancer Society which maps the history, current situation and some predictions for the future of the tobacco epidemic up to the year 2050. Designed by MyriadEditions, Ltd.,(http://www.myriadeditions.com), and written and compiled by Drs. Judith Mackay, Michael Eriksen and Omar Shafey, the atlas illustrates how tobacco is more than a health issue, involving economics, big business, politics, trade and crimes such as smuggling, litigation and deceit. The atlas also shows the importance of a multifaceted approach to reducing the epidemic by international organizations, NGOs, the private sector and the whole of civil society. The atlas can be found in its entirety at, and can be downloaded for free from: http://www.cancer.org/docroot/AA/content/AA_2_5_9x_Tobacco_Atlas.asp.

Click here to read: Lead Article | Q&A | CECHE News

Dr. Sushma Palmer, Program Director

Valeska Stupak, Editorial & Design Consultant

Shiraz Mahyera, Systems Manager

Rohit Tote, Website Consultant