Center for Communications, Health and the Environment

But, Major Challenges Lie Ahead

Q&A With Dr. Peter Salama

Dr. Peter Salama is Chief of Health, Associate Director, Programme Division, UNICEF, New York, N.Y.

1. UNICEF’s State of the World’s Children 2008 report states that the latest data (i.e., from 2006) show a dramatic reduction in under-five annual global mortality from almost 13 million in 1990 to 9.7 million. What causes of childhood mortality have shown the greatest reductions and which the least?

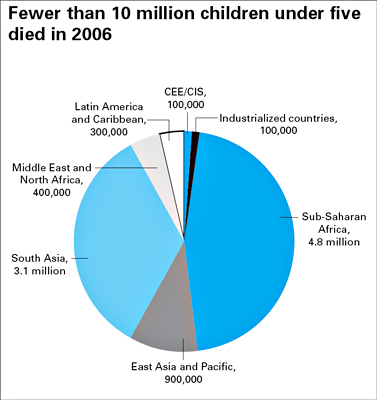

In 2006, for the first time in recent history, the number of children dying before their fifth birthday fell below 10 million – an important milestone in child survival. Around 1960, an estimated 20 million children under age five were dying every year, highlighting an important long-term decline in the global number of child deaths.

While we know the overall estimates of child mortality, the cause-specific information is not that often actualized, and we are continuously working with different groups and institutions to refine this information. We do know from the recent data that coverage of many key child survival interventions has significantly increased, with rises in some basic practices and services, including vitamin A supplementation, the use of insecticide-treated nets to prevent malaria, immunization, and early and exclusive breast-feeding, improving the health of children. Many of the statistics are encouraging. For example:

- More than four times as many children received the recommended two doses of vitamin A in 2005 compared to 1999.

- All countries with trend data in sub-Saharan Africa made progress in expanding coverage of insecticide-treated nets, with 16 of these 20 countries at least tripling coverage since 2000.

- In the 47 countries where 95 per cent of measles deaths occur, measles immunization coverage increased from 57 per cent in 1990 to 68 per cent in 2006.

- Rates of exclusive breastfeeding have significantly improved in 16 countries of sub-Saharan Africa over the past decade, with seven of these countries making gains of 20 percentage points or more.

- Progress has also been made in expanding coverage of antenatal care and skilled care at delivery – with every region showing improvements during the past decade.

- Between 1990 and 2004, more than 1.2 billion people gained access to improved sources of drinking water, and the world is on track to achieve the UN target for safe water.

These new figures show that progress is possible if we act with renewed urgency to scale up interventions that have proven effective.

2. Increased emphasis on vitamin A supplementation, measles prevention, prevention of mother-to-child AIDS transmission and exclusive breastfeeding are among the several interventions cited as major contributors to reduced child mortality, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. Have any interventions failed to show the anticipated impact, and if so, why?

We know from The Lancet series on child survival that all interventions we are scaling up are effective. Whilst we been successful in scaling up the “schedulable” interventions such as antenatal care, vitamin A supplementation, insecticide-treated nets and immunizations, some community-based interventions that rely on social and behaviour change, such as hand-washing, are showing a mixed picture. So, the coverage of some effective interventions is still too low to have the anticipated impact.

3. Which countries have benefited the most and which the least from interventions?

Several countries, including Egypt, Eritrea, Bangladesh, Brazil, Indonesia, Iran, Nepal and Vietnam, have reduced their under-five mortality rate by 50 per cent or more since 1990. Another set of countries, including China, Ethiopia, Haiti, Malawi and Mozambique, have decreased their under-five mortality rate by more than 40 per cent since then. Improvements in areas where rapid progress is being made, such as malaria and HIV, are not yet captured by these data, which are based on surveys conducted mostly in 2005; so the real picture is likely to be even more positive. These gains suggest that remarkable progress is possible, despite obstacles such as geographic location or socio-economic disadvantage, when evidence-based, sound strategies, sufficient resources, political will and an orientation towards results are consciously harnessed to improve children’s lives.

Of the 11 countries where 20 per cent or more of children die before age five – Afghanistan, Angola, Burkina Faso, Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger and Sierra Leone – more than half have suffered a major armed conflict since 1989. Similarly, fragile states, characterized by weak institutions with high levels of corruption, political instability and a shaky rule of law, are often incapable of providing basic services to their citizens. Countries that suffer from food insecurity or are prone to droughts are also at risk of having poorer child survival outcomes. The inability to diversify diets leads to chronic malnutrition for children, increasing their vulnerability to ill health and, ultimately, death

4. Why has progress in treating childhood illnesses such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and under-nutrition lagged behind reducing under-five mortality?

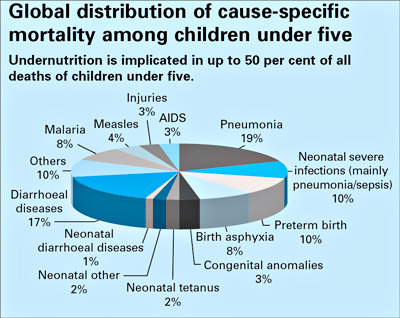

Pneumonia remains the most common cause of death in children under 5 years, taking the lives of more children than AIDS, malaria and measles combined. Yet, the percentage of children under 5 years with suspected pneumonia who receive antibiotics is dismally low – in Haiti for example, this proportion is only 3 per cent. And in sub-Saharan Africa, only 40 per cent of children with suspected pneumonia are taken to an appropriate health provider.

Under-nutrition results from an array of interrelated factors, including inappropriate feeding and care practices, inadequate sanitation, disease, poor access to health services, and weak knowledge of the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding practices and the role of micronutrients.

Low demand for quality health services among community members or the limited capacity of health facilities and extension workers to deliver essential services may restrict the coverage of intervention packages, as may financial, social and physical barriers to access. Meanwhile, weak health systems, the lack of adequate human resources and health facilities represent major barriers to scaling up integrated approaches to maternal, newborn and child survival, health and nutrition at the community level. In addition, families in the poorest countries, where the majority of children are affected, may not have easy access to health facilities. In-patient treatment may not be an option for parents who cannot leave their homes to accompany a sick child, and this is where well-supported community-based approaches can pay off, bringing treatment to people's homes, so that sick children can be identified and treated in a timely manner.

5. What lessons have been learned from evolving health-care systems and practices for providing primary health care to mothers, newborns and children?

An examination of different approaches to the delivery of essential services from the beginning of the 20th century to the present demonstrates:

- Scaling-up will not be achieved through facility-based services alone. Community partnerships are central to achieving coverage, creating demand and achieving sustainability.

- Vertical programmes have achieved impressive results by focusing on a narrow set of interventions and by monitoring results closely. However, unless systems are supported, those results will be circumscribed and may not be sustained. Ensuring a continuum of care by delivering integrated packages of health, nutrition, HIV, water and sanitation interventions will also be critical to achieving maximal impact on maternal, newborn and child survival.

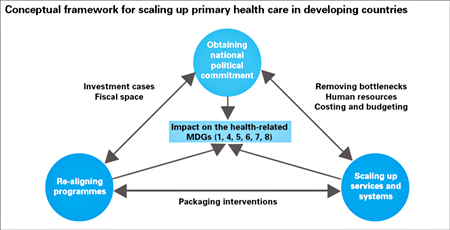

- The strengthening of ‘health-systems for outcomes’ has gained prominence in recent years as an effective and sustainable strategy for service delivery. This new approach combines the strength of selective/vertical approaches and comprehensive/horizontal approaches to health-care provision. It emphasizes the scaling-up of evidence-based, high-impact health, nutrition, HIV and AIDS, and water and sanitation intervention packages and practices, and underlines the importance of removing system-wide bottlenecks to health care provision and usage.

- No single approach to child survival and health is applicable in all circumstances. The organization, delivery and intervention orientation of health-care services must be tailored to meet the constraints of human and financial resources, the socioeconomic context, the existing capacity of the health system and, finally, the urgency of achieving results.

Data reproduced from: United Nations Children's Fund, The State of the World's Children 2008, Child Survival, UNICEF, New York, December 2007, pp 64.

Data reproduced from: United Nations Children's Fund, The State of the World's Children 2008, Child Survival, UNICEF, New York, December 2007, pp 64.

6. What do you see as the role of community partnerships in the continuum of care and health systems?

Empowering communities and households to participate in the health care and nutrition of mothers, newborns and children is a logical way of enhancing the provision of care, especially in countries and communities where basic primary health care and environmental services are lacking. As an integral part of the larger health system, community partnerships in primary health care can serve a dual function: actively engaging community members as health workers and mobilizing the community in support of improved health practices. They can also stimulate demand for quality health services from governments.

Community involvement fosters community ownership. It can also add vitality to a bureaucracy-laden health system and is essential in reaching those who are the most isolated or excluded. Community participation is viewed as a mechanism to reduce and eventually eliminate profound disconnections between knowledge, policy and action that impede efforts to address both the supply and demand sides of care. The importance of participation in health care, hygiene practices, nutrition, and water and sanitation services goes beyond the direct benefits to community members as they engage in activities that can impact positively on their health. It forms the heart of a rights-based approach to human progress.

7. How important are national and international partnerships, and partnerships between the private and public sectors in ensuring continuum of health care?

Partnerships at all levels and with all stakeholders are key for accelerating progress towards the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). UNICEF is working closely with United Nations system partners and with governments, regional and non-governmental organisations, foundations, civil society and the private sector to coordinate activities and to pool expertise and knowledge.

Initiatives and partnerships directed towards improving aspects of maternal, newborn and child health abound and continue to proliferate, with initiatives such as the H8, “International Health Partnerships” and “Harmonization for Health in Africa” starting to address coordination, coherence and harmonization among these partnerships and initiatives.

The basis for action – data, research, evaluation, frameworks, programmes and partnerships – is already well established. It is time to rally behind the goals of maternal, newborn and child survival and health with renewed vigor and sharper vision, and to position these goals at the health of the international agenda. Our challenge now is to act with a collective sense of urgency to scale up that which has proven successful.

8. Can you give some examples of organizations that are doing notable work to improve the state of the world’s children, and what are they doing that is making such a difference?

Many organisations are doing notable work. Some are governments, some are donor organisations, others are non-governmental organisations or sister UN agencies, and all contribute to the achievement of the MDGs in their own ways. For example, the Global Alliance on Vaccines and Immunization (GAVI), the Global Fund to Fight Aids, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have mobilized important new resources for major health threats, and have brought much needed political and technical focus to priority diseases or interventions. They have injected new energy into development assistance by supporting the private sector.

Another example is the Measles Initiative, a partnership launched in 2001 that groups UNICEF and WHO with other leading international agencies and prominent private organisations. The main sponsor of the mass campaign to boost measles vaccination, the Measles Initiative shows how a well resourced, targeted and managed global vertical programme can reach scale rapidly and produce dramatic results: More than 217 million children were vaccinated between 2001 and 2005 – mostly in Africa, and the results exceeded the UN target as measles deaths fell by 60 per cent between 1999–2005, with Africa contributing 72 per cent of the absolute reduction in deaths. Estimates concluded that immunization helped avert almost 7.5 million deaths from the disease.

9. How relevant are the findings of the UNICEF report to industrialized nations such as the United States?

We believe the findings of The State of the World’s Children 2008 are relevant to all countries in the world. Global and national numbers are important, but they do not always tell the entire story. Many countries have inequity issues when it comes to health, and the document highlights some of those inequalities that need to be corrected, including adequate nutrition and hygiene; sufficient, skilled delivery and newborn care; and access to basic immunizations, micronutrient supplements and other therapies to combat disease and boost immune systems. The report is also an important tool to inform people all over the world about the status of all children and their needs.

In addition to The SOWC 2008, publications from the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre in Florence discuss the status of industrialized nations in great depth. Innocenti Report Card 7, “An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries,” released last year, for example, provides a comprehensive picture of child well-being in economically advanced nations through the consideration of six dimensions: material well-being; health and safety; education; peer and family relationships; behaviours and risks; and young people’s own subjective sense of well-being. The report card shows that among all of the 21 OECD countries assessed, from the overall top-ranking Netherlands to the bottom-ranking United States and United Kingdom, there are improvements to be made and that no single OECD country leads in all six areas. (To access Report Card 7, go to http://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/article.php?type=3&id_article=49 and click on the link.

10. Can you shed some light on special approaches that might be needed to improve child survival and maternal well-being in industrialized nations?

The problems in industrialized countries might be different, but there always will be behaviours that can be improved, as outlined in Innocenti Report Card 7. We have learned from many countries, for example, that the community component to health is extremely important, especially when it comes to communication for social and behaviour change. It therefore behooves all nations to support current as well as burgeoning community partnerships, and to pursue the development of new such initiatives. Perhaps we also need to learn more about social networks and their role in industrialized countries and see how we can build on these to provide to mothers and children in need.

While there’s no definitive approach or solution, the answer to improving child survival and maternal well-being, especially in industrialized countries, may lie in the maxim, “To improve something, first measure it.” The decision to measure helps set directions and priorities by demanding a degree of consensus on what is to be measured – and what constitutes progress. Over the long-term, measurement serves as the handrail of policy, keeping efforts on track towards goals, encouraging sustained attention, giving early warning of failure or success, fuelling advocacy, sharpening accountability, and helping to allocate resources more effectively. In short, a multi-dimensional approach to well-being is necessary in industrialized and developing countries alike – one that encourages monitoring and measurement, permits comparison, and stimulates the discussion and development of policies to improve the lives of mothers and children.

11. What do you see as the biggest challenges over the next decade to achieving the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the majority of which pertain to children?

It’s a formidable list: poverty; inequalities in child survival; conflict; and the scaling-up of community-based interventions that rely on social and behaviour change.

Poverty excludes millions of women and children from progress. The inequalities in child survival between poor and better-off children are stark. For countries with available data, children in the poorest 20 per cent of households are far more likely to die before their fifth birthday than children living in the richest quintile. Meanwhile, access to basic interventions remains spotty; all children, their mothers and communities deserve access to effective interventions, including new technologies such as new vaccines, artemisinin-based combination therapy, zinc and antibiotics, and their provision will be crucial going forward if the MDGs are to be achieved. Wars and internecine conflicts cripple a nation’s ability to focus on issues of public health and provide basic services; and they impede, if not destroy, progress on every level.

Scaling-up existing interventions is also critical to accelerating progress on the health-related MDGs for children and women – particularly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, which together accounted for more than 80 per cent of all child deaths in 2006. Scaling-up involves a complex range of actions, many of which are interrelated, to both achieve breadth and ensure the long–term sustainability of the expansion. At the programmatic and policy levels, it is not enough simply to expand the delivery of packages of low-cost, proven interventions: behavioural, institutional and environmental impediments that can impede access must also be addressed as part of the scaling-up process. Success requires an in-depth understanding of these obstacles, as well as of the strategies for circumventing them.

12. What, in your opinion, are the biggest takeaways from this UNICEF report? The biggest disappointments?

While recent data show a fall in the rate of under-five mortality, there are still too many children dying every year. The SOWC 2008 goes beyond the numbers to suggest actions and initiatives that should lead to further progress. It looks at several of the most promising approaches – community partnerships; the continuum of care framework; and health-system strengthening for outcomes – all aiming at reaching those mothers, newborns and children who are currently excluded from essential interventions.

The SOWC 2008 examines these lessons and highlights the most important emerging precepts, including:

- The need to focus on the countries and communities where child mortality rates and levels are highest, and on those that are most at risk of missing out on essential primary health care.

- The merits of packaging essential services together to improve the coverage and efficacy of interventions.

- The vital importance of community partnerships in actively engaging community members as health workers and mobilizing the community in support of improved health practices.

- The imperative of providing a continuum of care across the life cycle, linking households and communities with outreach and extension services and facility-based care.

- The benefits of a strategic, results-oriented approach to health-system development with maternal, newborn and child care as a central part.

- The crucial role of political commitment, national and international leadership and sustained financing in strengthening health systems.

- The necessity for greater harmonization of global health programmes and partnerships.

Click here to read: Lead Article | Q&A | CECHE News

Dr. Sushma Palmer, Program Director

Valeska Stupak, Editorial & Design Consultant

Shiraz Mahyera, Systems Manager

Rohit Tote, Website Consultant