Center for Communications, Health and the Environment

THE ECONOMICS OF OBESITY:

Excessive Weight Gain Taxes Individuals, Nations, Environment

Obesity exacts a heavy toll worldwide. And payment is not just in the form of poor personal health and a series of debilitating and potentially fatal health problems, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke. Being obese has significant financial implications, from lower and lost income to added personal, public and even environmental costs.

Lower Income

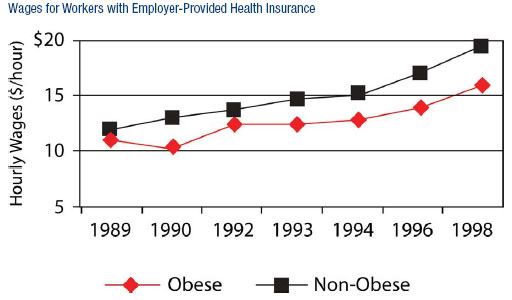

According to Stanford University researchers, obese U.S. men and women earn, on average, $3.41 per hour less than their peers. This translates into $7,093 in lost annual income per obese person. In 2005, the National Bureau of Economic Research revealed that the income gap increases as these employees age, and that obese workers are paid less when they have employer-sponsored health insurance, because, research shows, they pay in the same premiums as thinner employees, but have higher medical expenses (between 29 and 117 percent higher, according to the Centers for Disease Control). Obese white women may suffer most, at least in the United States, where, reports John H. Cawley of Cornell University, a weight of 64 pounds above the average for white women was associated with 9 percent lower wages.

Overweight and obesity are also linked to poor academic performance, according to researchers at University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health. In addition, heavy people tend to accumulate less overall wealth: A 2004 study by Dr. Jay Zagorsky of The Ohio State University compared net worth with BMI (body mass index) scores and found obese Americans to be approximately half as wealthy as thin ones.

|

Lost Productivity, Lost Income

Obese workers also lose an average of a week of work a year because of weight-related ailments, reports the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. In fact, a company of 1,000 employees loses $285,000 annually due to obese workers, and 30 percent of that (or $85,500) is because of increased absenteeism, note Eric A. Finkelstein and Laurie Zuckerman in their 2008 book, The Fattening of America.

Meanwhile, in Australia, for example, an estimated $1.7 billion is lost annually from a drop in output caused by reduced employment and premature death of obese individuals, according to a 2006 Access Economics analysis commissioned by Diabetes Australia. Such statistics cause Student BMJ authors Hannily Harvey and Janneke Patterson to muse that “A nation’s developmental gains could...be undone by a large reduction in the people’s capacity to work.”

Higher Personal Costs

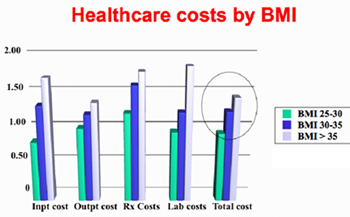

Excessive weight also taxes personal gains. Overweight U.S. males, for example, pay $170 more in medical costs annually than their leaner co-workers, while the costs for overweight U.S. females are $495 higher, point out Finkelstein and Zuckerman. In 2002, spending on medical care related to obesity accounted for 11.6 percent of all private health care spending, compared with 2 percent in 1987, and the numbers keep rising. In fact, between 1987 and 2002 alone, the share of private health spending attributable to obesity soared more than tenfold, from $3.6 billion to $36.5 billion, according to a study published online in the journal Health Affairs. In addition heavy people pay two to four times more for life insurance premiums than “normal-size” individuals.

Even travel costs more. In mid-April, for example, United Airlines began requiring people needing a second seat because of their size to pay more for the extra seat; and starting in 2002, budget airline Southwest began enforcing its 22-year-old policy requiring overweight or obese passengers who need all or part of two seats to purchase two tickets. Clothing expenses are also higher, as tall and plus size products tend to cost more than average sizes to cover the expense of the extra materials.

Meanwhile, in developing countries like India, obesity-related conditions such as diabetes are depleting the assets of, and in some cases even bankrupting, scores of middle-class urbanites, who may spend more than a quarter of their incomes on diabetic treatments because of a nationwide lack of medical insurance.

Higher Public Costs

And then there are the increased costs to society.

In the United States: These increased costs amount to a whopping $93 billion annually, says Finkelstein.

According to Dr. Kelly D. Brownell and Dr. Thomas R. Frieden in an April 2009 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), an estimated $79 billion is spent every year just on health care related to overweight and obesity, “and approximately half of these costs are paid by Medicare and Medicaid, at taxpayers’ expense.”

|

A 2004 Economics of Obesity report by Jay Bhattacharya of Stanford University and Neeraj Sood of the RAND Corporation details that “the lifetime medical costs related to diabetes, heart disease, high cholesterol, hypertension, and stroke among the obese are $10,000 higher than among the non-obese.”

Meanwhile, as reported in a December 2006 article in the monthly insurance magazine Best’s Review, “Kaiser Permanente studies show that a weight gain of 20 pounds results in more than $500 per person of increased costs over the next three years...So anytime someone gains some weight, there's cost to the health-care system."

In California, the cumulative costs of physical inactivity, obesity and overweight among the state's workers was $21.7 billion in 2000, with physical inactivity totaling $13.3 billion, obesity $6.4 billion, and overweight $2 billion, according to a 2005 report. The report found that about three-quarters of the costs – more than $16 billion – were assumed by public and private employers in the form of health insurance and lost work productivity. (It also contended that if one or two of every 20 overweight and/or sedentary Californians became leaner and more physically active, the state could save about $1.3 billion per year.)

On the opposite coast, New York spends $6.1 billion each year to treat obesity-related health problems, according to recent statistics released by the state governor’s office.

In addition to the increasing financial burden on national and state health care coffers, hospitals have to pay more to treat the obese. Oversized wheelchairs can cost about $2,500, eight times the cost of an ordinary wheelchair, explain Finkelstein and Zuckerman in The Fattening of America, and operating tables that are strong enough to support the severely obese can run as much as $30,000.

Around the Globe: Obesity could cost the global economy as much as malnutrition, warns the World Bank. In 2001, Barry Popkin and his colleagues at The Food Policy Research Institute reported that China sacrificed more than 2 percent of its gross domestic product to cover the costs of diet-related chronic diseases – more than it spent on undernutrition. By August 2006, Popkin noted in National Geographic News that the cost to China of poor diet, physical inactivity and obesity was now up to 5 percent of the country’s gross national product (GNP), and that it was only “a matter of time” before obesity-related spending there caught up to that of the United States, “which spends 17 to 20 percent of its GNP” on such costs.

According to a November 2006 Natural News article, 6 percent of health costs in the World Health Organization's European region are a result of obesity in adults. For example, obesity cost France $6.41 billion in direct outlays in 2002, and in July 2008 following publication of Britain’s largest obesity study, the country’s health secretary estimated that obesity-related costs to Britain’s National Health Service were likely to rise sevenfold by 2050. Meanwhile, including indirect costs, the price tag for obesity in Australia was an estimated $21 billion and $58 billion in 2005 and 2007, respectively, based on studies commissioned by Diabetes Australia.

One special concern is that obesity-related costs could overwhelm the health care systems of developing countries. This may especially apply to China and India, which are already reeling from outlays associated with communicable diseases and malnutrition, and where, according to the World Bank, average per capita health expenditures “are less than 10 percent of expenditures in developed countries,” explain Stacey Rosen and Shahla Shapouri in their September Amber Waves article, “Obesity in the Midst of Unyielding Food Insecurity in Developing Countries.”

Environmental Costs

In addition to personal and public pocketbooks, obesity taxes the environment. Heavier passengers burn more fuel, for example. According to a 2004 Centers for Disease Control report, Americans' average weight increased by 10 pounds in the 1990s, causing airlines to spend $275 million on an additional 350 million gallons of fuel to support that extra weight. And a 2006 study published in The Engineering Economist found that Americans pumped 938 million more gallons of fuel a year than they did in 1960 because of their “heftier frames.” This increased annual gas expenditures nationwide by $3.55 billion (and added to environmental pollution).

Double Jeopardy

Becoming obese may itself be a question of economics, at least for certain segments of society. In their January 2006 commentary in Nature Medicine, Derek Yach, David Stuckler and Brownell cite five factors that have “tipped the balance between caloric intake and expense to an unfavorable equilibrium.” They are:

- Expanding labor market opportunities for women

- Increased consumption of food away from home

- Decreased requirements of occupational and environmental physical activity

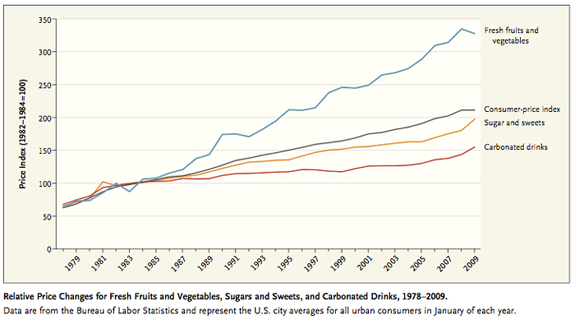

- Rising costs of healthy foods relative to unhealthy ones

- Growing quantity of caloric intake with declining overall food prices.

The “economics of food choice” figure particularly prominently in the obesity equation, contend Adam Drewnowski and Nicole Darmon in a 2005 article in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. In short, people use price as a guide to food shopping. In simple terms, sweets and fats cost less, whereas vegetables and fruits cost more, so more and more people are opting for less expensive energy-dense simple carbohydrates over healthier legumes – and putting themselves at risk for obesity.

|

That’s not to say that unhealthy food is cheap. Snacks, soda, desserts and prepackaged ready-to-cook foods are not only calorie-dense and laden with sugar, fats, and salt, but many prepackaged meals are also much more expensive than freshly prepared ones. It is a cost associated with convenience, as freshly prepared food entails more physical activity and energy expenditure than oven-ready dishes.

Nevertheless, studies conducted in Australia, Canada and the European Union have found that healthier diets cost more, and studies of increases of the number of obese adults in the United States (Lakdawalla and Philipson 2002; Chou, Grossman, and Saffer 2004) reveal that much of America’s obesity trend can be attributed to lower prices, reports the September 2008 issue of Today’s Research on Aging. The same publication points to research that shows that the drop in food prices between 1980 and 2005 may have accounted for up to 40 percent of the increase in BMI since 1980.

“[T]he changing incentives that people face have conditioned unhealthy choices to become the economically smarter choices,” note Yach, Stuckler and Brownell. Finkelstein agrees. “Modern society is giving Americans many more incentives to gain weight than to lose it,” he quips in a February 2008 interview, citing new technologies and the “abundance of cheap, tasty foods” as “the two most obvious factors.” Meanwhile, he notes, the health costs of obesity are actually declining: “...research by the Centers for Disease Control reveals that today’s obese population has better blood pressure and cholesterol values than normal-weight adults did 30 years ago...[and] if the costs of being obese go down, and there are people who like to eat and don’t like to exercise, we are bound to see obesity rates go up.” Which, apparently, is what has happened.

Fat-cutting Measures

Past efforts suggest that “information-based strategies...will have a limited impact” in tackling the problem of obesity, contend Finkelstein, Christopher Ruhm and Katherine Kosa in “Economic Causes and Consequences of Obesity.” And most experts agree.

Success on the obesity front will require multifaceted interventions – and fiscally driven ones.

According to Yach, Stuckler and Brownell, “market-led solutions, along with public policies, may combine to make healthy choices the economically easy and readily available choices.” They discuss the development of country-specific roadmaps to determine which approaches would have the greatest national impact.

In The Fattening of America, Finkelstein and Zuckerman argue that in the United States “the government should revisit past policies that may have inadvertently helped promote the rise in obesity rates.” They point to agricultural subsidies for farmers, zoning laws that discourage pedestrian transportation, subsidies to employers for providing health insurance, and even the existence of the Medicare program. And then there are the 30-year-old national nutrition standards in effect in the vast majority of U.S. public schools. These standards prohibit the sale of seltzer water, but include pizza, doughnuts and cheeseburgers, as well as vending machines hawking soda and junk food, on school menus and in school buildings.

Past policies should certainly be reevaluated, but new measures need to be instituted to reduce the costs – physical, social and economic – of obesity worldwide. Proposed market and policy options around the globe include higher taxes on unhealthy foods and beverages; the regulation of fast foods and food advertising; and the mandatory inclusion of calories on restaurant menus on more than a local level.

Taxing Unhealthy Eating

Studies show that cost matters. So targeting people’s pocketbooks may be a sound first step both to curbing the consumption of unhealthy items and to generating funds to implement additional obesity-battling measures. Such an approach would feature price changes and taxes, as well as financial incentives. It may also benefit people who can most afford choice, unless in the process of making unhealthy foods financially unappealing, the prices of healthier items are reduced or subsidized to allow those segments of the population most affected by the relationship between price and obesity to afford to make healthy choices. Everybody must eat, but the cost of basic food products needs to remain in line with the average person’s paycheck.

In a 1999 study conducted in China and published in The Journal of Nutrition,” Xuguang Guo, Barry Popkin, Thomas A. Mroz and Fengying Zhai found that an increase in the price of an individual food group led to significant reductions in the probability of consuming any food within that food group – and on the quantity of food consumed. For instance, price changes for animal protein foods had a large effect on reducing fat intake, a primary contributor to obesity in China. Since people, especially those facing economic constraints, tend to forego more expensive foods for less expensive ones, increasing the cost of foodstuffs that play a pivital role in the development of obesity, such as animal proteins, fats and sugars, while simultaneously demonizing them in a cultural context, could limit their consumption.

A price-policy approach would be both technically and politically complex to execute, but it is, nonetheless, a viable option – one that must take into account cultural and socio-economic tendencies. In Scandinavia, for example, aggressive state policies related to taxation and import tariffs are believed to have had an effect on dietary choices and public health (Milio 1990 and 1991). And Yach, Stuckler and Brownell remind us that high taxes on cigarettes have proven to be one of the most effective ways of reducing smoking rates. “Data indicate that higher prices also reduce soda consumption,” note Brownell and Frieden; they cite a review by Yale University’s Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity suggesting that for every 10 percent increase in price, consumption decreases by 7.8 percent, as well as an industry trade publication report revealing that as prices of carbonated soft drinks increased by 6.8 percent, sales dropped by 7.8 percent.

Taxes and tariffs in particular can also generate substantial revenue while conferring health benefits – especially when applied to heavily consumed items. According to Brownell and Frieden in their 2008 NEJM “Ounces of Prevention — The Public Policy Case for Taxes on Sugared Beverages,” something as seemingly insignificant as a penny-per-ounce excise tax on such drinks would raise an estimated $1.2 billion in New York State alone. This money could fund anti-obesity efforts, including healthy food programs, but, they emphasize, “only heftier taxes will significantly reduce consumption.” Nonetheless, even this penny-per-ounce excise tax could reduce consumption of sugared beverages by more than 10 percent – results an education campaign would be hard-pressed to deliver.

The Means to Motivate

Insurance premiums tied to weight could also encourage healthier living. Bhattacharya and Sood, for example, found that health insurance that allows underwriting on weight, and in which premiums are a function of weight, may help to curb obesity because consumers are given financial incentives to shed pounds in the form of lower premiums. “Because consumers face the full costs of their weight choice through the health insurance premium, they choose to lose weight even when fully insured,” they explain, noting that this does not happen with full insurance, when underwriting on weight is not allowed.

|

Employers too could play a key role in supporting healthy lifestyles and reducing obesity by “promoting wellness in their workforce.” In fact, companies that bankroll workplace health promotion programs reap average “savings of $3 for every $1 invested,” report Yach, Stuckler and Brownell. That may be one reason why, according to Dr. Susan Okie in her 2007 NEJM article, “The Employer as Health Coach,” many of today’s larger companies, like General Mills, are tackling employees’ bulging waistlines and burgeoning medical bills through annual health risk assessments and a host of health-related offerings such as free preventive services at work, subsidized corporate cafeterias that serve nutritious, low-calorie choices, and even on-site medical clinics, gyms and pharmacies. To encourage workers with chronic diseases to take medication, for example, Pitney Bowes reduced co-payments on all drugs for hypertension, asthma and diabetes to 10 percent; and while the company's spending on these drugs increased, its overall costs for the three diseases dropped and its health costs per employee were reported to be roughly 20 percent below those of comparable employers.

The Bottom Line

The economic rationale for public policy action in the case of obesity is clear. So why isn’t more being done?

According to Yach, Stuckler and Brownell, the areas of food, nutrition and physical activity are far-reaching and complex. They comprise numerous vested, and monied, interests, including governments, politicians, health care systems, insurance giants, multibillion-dollar food companies, the fitness industry, and billions of independent-minded consumers. The stakes are high, and real progress will require broader alliances and stronger bonds between public, private and civil societies.

Forging those bonds is imperative if effective intervention is to take place and the cumulative costs of obesity are to be controlled, capped and curtailed. Otherwise, “the costs of obesity might well become catastrophic,” laments Dr. David Ludwig of Harvard Medical School in the NEJM. And the sacrifice of human life and productivity would be immeasurable.

Read More:

Lead Article: Obesity and Overnutrition Trump Undernutrition in Newly Affluent Nations

In the Spotlight: The Economics of Obesity

CECHE News: CECHE Promotes Healthy Hearts

Also Noted: Is Obesity Contagious?

Dr. Sushma Palmer, Program Director

Valeska Stupak, Editorial & Design Consultant

Shiraz Mahyera, Systems Manager

Daniel Hollingsworth, Website Consultant