Center for Communications, Health and the Environment

Biotech Crops Gain Global Foothold

Genetically engineered, or modified, foods are a mainstay in middle America. In fact, the United States is the number-one producer of transgenic crops, and experts say that as much as 60 to 70 percent of processed foods on U.S. grocery shelves contain genetically modified (GM) ingredients. While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does regulate GM foods and applies the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act to ensure that foods made from biotech crops are safe for human and animal consumption, it does not require food from GM animals or plants to be labeled as such.

In many other countries, genetically engineered (GE) foods are controversial, micromanaged, and even banned. Europe, in particular, has been ground zero for heated debate, and recent protests in India emphasize that GM foods are hardly a foregone conclusion. Yet, worldwide production of such crops, and demand for them, is on the rise.

Global Upswing in GM Crops

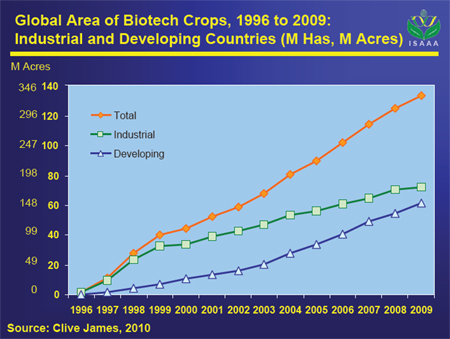

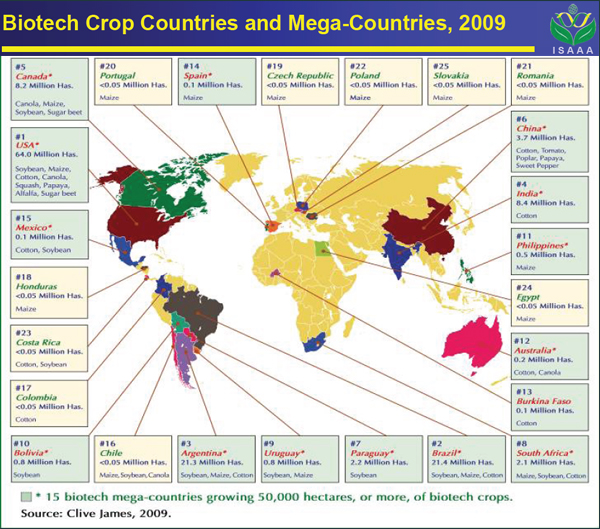

Between 1996 and 2009, there was an unprecedented 80-fold increase in global biotech crop acreage, with total accumulated acreage for the 13-year period topping 2 billion acres, according to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) in its “Highlights of ‘Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2009’ ” by organization founder Clive James. In 2009 alone, a record 14 million farmers in 25 countries that together house more than half the world’s population planted 330 million acres of GM crops, an increase of 7 percent or 22 million acres over 2008, the service reports. Today, more than three-quarters of the soybeans grown around the world are genetically modified, as is nearly 50 percent of the cotton and more than a quarter of the corn. Developing countries, including Brazil, Argentina, India and China, now account for almost half of the global acreage of these and other biotech crops – and are expected to usurp the lead from industrial countries over the next five years.

|

| Source: International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) |

By 2015, the ISAAA predicts 20 million biotech crop farmers and more than 490 million acres of biotech crops in 40 countries. Meanwhile, the United Nations (UN) projects the world’s population will top 9 billion by 2050, requiring a 50 to 70 percent rise in global food production to feed all inhabitants in conjunction with anticipated crop failures, according to the International Food Policy Research Institute and the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization respectively. Climate change will impose further challenges on agriculture’s ability to meet food demands, particularly in the developing countries of Asia, Latin America and Africa, and new advances in food technology may offer both hope, and help.

China

|

| Testing for GM Rice in China (Source: Greenpeace) |

Nowhere is the need to feed a burgeoning population as apparent as in China.

The Asian giant is currently home to more than 1.3 billion people – more than 20 percent of the world’s population; yet it contains only 7 percent of the world’s productive land, with an ever-increasing portion of that land being lost to development and drought. GM pest-resistant cotton is already grown on an industrial scale in China, and the country continues to invest hundreds of millions of dollars in biotech crop research and development.

Meanwhile, in a landmark decision in November 2009, China approved a nationally developed proprietary insect-resistant rice variety, as well as a biotech phytase maize (corn), for full commercialization in about two to three years (pending completion of standard registration field trials). Since rice is, according to the ISAAA, “the most important food crop in the world,” this decision could directly benefit 110 million rice households (or 440 million people, assuming an average of four per family) in China and another 250 million rice households across Asia – an estimated 1 billion people. It could also mean great improvements in both productivity and standards of living for the world’s impoverished rice farmers – delivering benefits (in the form of higher yields, greater productivity, and savings on pesticides and fertilizers) of $4 billion a year, while offering environmental benefits through the reduced need for broad-spectrum pesticides. At the same time, biotech phytase maize could directly benefit 100 million households (400 million people) across China, the ISAAA reports, and will play an important role in feeding the country’s 500 million pigs (half of the global swine population) and 13 billion chickens, ducks and poultry, while reducing pollution from lower phosphate in animal waste.

Following up on the move towards large-scale GM planting, in January 2010 in its "Number One Document,” an annual agenda-setting publication issued jointly by the ruling Communist Party and State Council, China listed the development of new GM crops as one of 16 major projects in its plan for scientific and technological development until 2020. In addition to GM rice and phytase corn, the government's plans include the development of pest- and disease-resistant GM rapeseed and soy, with research focusing on yield, quality, nutritional value and drought tolerance, according to a February 2010 article by Chen Weixiao on SciDev.Net. But will China’s recent policies on GM foods be supported by strong science, management and legislation enforcement to curb unnecessary, and potentially damaging, risk-taking?

India

|

| Death procession of Bt Brinjal in Jhabua, Madhya Pradesh Source: http://www.i-sis.org.uk/gmProtestsIndia.php. ISIS Report 30/04/08. © 1999-2010 The Institute of Science in Society |

India too has been reeling from recent decisions involving GM foods. Overturning a previous ruling by an official scientific advisory body, in February 2010, the Indian government issued a moratorium on the development and commercial release of Bt Brinjal, a GM eggplant engineered with a gene from the soil bacterium bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) to produce its own insecticide. Bt Brinjal was to be India’s first biotech food crop, and, according to a February 11, 2010 Economist article, supporters of the product claim that it could reduce losses from insect damage by more then 50 percent and cut pesticide usage by 80 percent.

Meanwhile, India remains a significant producer of GM cotton, upping its adoption of the engineered product from 80 percent in 2008 to 87 percent in 2009, according to the ISAAA. Its success with GM cotton has revolutionized national cotton production, helping to transform the developing country from a cotton importer to a major exporter.

It has also been a boon for India’s biotech cotton farmers, who, the ISAAA reports, reaped an accumulated economic benefit of US$5.1 billion from 2002 to 2008. GM cotton has also cut insecticide requirements in half, and has contributed to a doubling of yield, the service notes.

Africa and Other Developing Nations

Despite reluctance on the part of many of the continent’s leaders, biotech crops are also expanding their footprint in Africa. Egypt is encouraging the use of the technology. And South Africa recorded a 17 percent growth in overall GM crop production in 2009, according to the ISAAA, while GM cotton acreage in Burkina Faso increased 1,353 percent, from 21,000 acres in 2008 to 284,130 acres in 2009, the highest proportional increase worldwide last year.

Meanwhile, American biotech giant Monsanto is donating its drought-resistant technology to the coalition Water Efficient Maize for Africa in an unusually generous move for Western agribusiness, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is funding research on a biofortified sorghum that could improve the nutritional status of millions of Africans, who rely on the grain for most of their calories.

As GM crop production headlines in Africa, it continues to flourish in South America. Regional giants Brazil and Argentina are currently the second and third largest growers of biotech crops worldwide after America, cultivating a combined total of more than 105 million acres. In 2009, Brazil recorded the highest absolute growth in biotech acreage for any country in the world, with its 13.8 million-acre increase equivalent to a 35 percent year-over-year growth between 2008 and 2009, the ISAAA reported. According to a February 25, 2010 article in The Economist, Brazil’s prominence on the GM foods front is due in large part to the government’s investment in local research centers. These include the Brazilian Agricultural Research Cooperation, Embrapa, which in December 2009 received approval for the country’s first locally developed GM crop, an herbicide-tolerant soybean created in partnership with German chemical behemoth BASF. Also among the globe’s top eight biotech crop countries last year was Paraguay, with more than 5 million acres, and Uruguay, Bolivia, Chile and Colombia are active producers as well.

|

Source: International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) Click Image to Enlarge |

The European Union and the GM potato

While GM crops are being embraced by South Americans, Europeans have largely rejected them on the grounds that they pose potential ecological and health issues. The fact that Europe boasts scores of small farmers who were more threatened than thrilled by the advent of transgenic crops has also impacted adoption, as has the lack of a strong central regulator, like America’s FDA, to “bless” the technology and provide public peace of mind, noted Kenneth Klee in the September 1999 Newsweek article, “Frankenstein Foods?”.

Of the 26 European Union (EU) countries, only six plant insect-resistant corn/maize, which is the only GM crop accepted there. In 2009, these six nations planted 234,132 acres, 9 to 12 percent less than in 2008, the ISAAA reports, with Spain growing 80 percent of all EU GM maize. Meanwhile, another six EU member states — Austria, Hungary, France, Greece, Germany and Luxembourg — ban the cultivation of GM maize on their territories, despite the fact that these bans were declared illegal in a 2006 World Trade Organization ruling that said the national safeguards were not based on scientific assessment of the risks, as required.

At the same time, Europe’s demand for soy has genetically modified organisms (GMOs) knocking on the continent’s door. According to the March 2010 TIME online article “Is Europe Finally Ready for Genetically Modified Foods?” by Leo Cendrowicz, Europe “has no choice but to import GMOs, since 75% to 80% of the global soya crop is from transgenic breeds.” Current EU rules are tough, however: Any produce with more than 0.9 percent GM content must be labeled accordingly, and GM foods must be separated out of the supply chain to prevent contamination of organic food. This has many EU businesses crying “foul,” and claiming that the Union’s strict policies, and general nonacceptance of GMOs, are hurting business, undermining potential profits and causing European agriculture, as well as EU farmers, to “lose ground against rivals,” the TIME article reports, noting that reticence regarding GM foods runs contrary to EU support for innovation and technology, and its birthing of some of the world’s biggest biotech groups.

Regulations aside, Europe is sure to see an uptick in GM crop production this year. That’s because in early March 2010, the EU authorized the cultivation of GM potatoes, breaking a 12-year moratorium. Created by BASF (an ironic twist, since Germany discontinued GM planting in 2008), the GM potato is not intended for human consumption. It has been developed to produce higher levels of starch for use in industries like paper manufacturing. Austria has already said it will outlaw growing the potato, and Italy appears to be following suit. Meanwhile, according to an April 2010 article by Philip Case of UK-based Farmers Weekly Interactive, 17 GM products await approval for cultivation in the EU, and 46 others are looking for permission to be used for food and feed, and to be imported and processed there.

The “Business” of Biotech Foods

Despite European reluctance as exemplified by Austria and Italy’s potato protestations, big firms are realizing significant profits selling GM seed. According to industry consultancy Cropnosis, the market for agricultural biotechnology more than doubled between 2001 and 2006, from about $3 billion to more than $6 billion. In 2009 alone, the global GM seed market was worth US$10.5 billion, and GM crops were valued at more than US$130 billion, as estimated by Cropnosis and reported by the ISAAA. At the same time, it is becoming more and more expensive (and perhaps even foolhardy), for farmers, and countries, to avoid GMOs.

In their recently released survey, Graham Brookes and Peter Barfoot of the agricultural and food economics consultancy PG Economics calculate that the global net economic benefits to biotech crop farmers in 2008 amounted to US$9.2 billion, divided almost equally between developing and developed countries. Meanwhile, the accumulated benefits from 1996 to 2008 were US$51.9 billion, in another near-even split between developing and industrialized nations. Of these economic gains during the 12-year period, 49.6 percent were due to substantial yield increases, and 50.4 percent were a result of a reduction in production costs, the survey reports.

Yet the prices farmers must pay for GM seed keep increasing, due in part to rising licensing royalties by companies like Monsanto, the world’s largest seed producer, which, from 2005 to 2009, recorded five straight years of revenue and profit growth, reporting net gains of US $2.1 billion on revenues of US $11.7 billion in 2009. Still, according to Brookes and Barfoot, the total average cost to farmers worldwide for accessing GM technology across the four main biotech crops (soybean, maize, cotton and canola) in 2008 was “equal to 27% of the total technology gains.”

But the “business” of GM foods amounts to more than company profits, and producer costs and returns. GM crop benefits vary, are not necessarily universal – and may be overrated.

Several studies do show that GM cotton farmers in India and China have higher yields and increased income, and that their use of Bt cotton increases the yields of neighboring non-GM cotton farmers through a spillover effect. For example, one study released by The Associated Chambers of Commerce and Industry of India and reported on by Monsanto found farmers planting biotech cotton recorded a gross revenue benefit of 162 percent and used less pesticides. But many small-scale farmers in India and China do not spray pesticides, so using engineered cotton may not significantly reduce pesticide use overall in these countries.

GMOs may also put crops at risk for greater catastrophic failure, since the process of cultivating GMOs encourages monocropping, instead of crop rotation, notes an April 2010 article on Aetna’s InteliHealth Web Site. When this practice is coupled with the pesticides in GM plants, crops can become more vulnerable, and resistance in targeted pests may develop over time. Both GM corn in Africa and biotech cotton in India have suffered crop problems and failures in recent years that may be related to the current process of growing GMOs. Furthermore, the Institute of Science in Society, a UK nonprofit, has reported allergic reactions by Indian farmers and workers as well as animal illnesses and deaths related to the country’s Bt cotton fields; it has also noted alterations in the ecology of cotton pests, so that Bt cotton farmers are dealing with newer pests and diseases that may promote pesticide use.

The Global Future of GM Foods

GMOs are still relatively new, and their long-term effects on the environment, livestock and humans are unknown. Yet proponents tout GM crops as the obvious answer to the globe’s growing food needs, pest problems and commercial constraints, brought on in large part by increasing population density and public coffers in China and India coupled with dwindling land, water and energy resources. GMOs could, they say, offer the higher yields and reduced resource needs necessary to circumvent looming issues, especially given the current lack of documented risks and the plethora of quantifiable benefits associated with biotech crops. Skeptics aren’t so sure, and organizations like the “Coalition for GM Free India” diligently monitor biotech crop production and work to raise awareness and foster an informed debate on GMOs.

Continuing to discuss and scrutinize the existence, distribution and development of GM crops is both critical and responsible. Meanwhile, the unveiling of more GM varieties and the planting of biotech crops proceed at a seemingly breakneck pace. And “multinationals are not the only game in town,” reminds a February 25, 2010 Economist article.

China, India and Brazil are in the thick of future GM crop developments –with China significantly increasing agricultural research as it pushes forward with the development of several new GM crops and full commercialization of its nationally developed proprietary rice variety and a biotech phytase maize, while India and Brazil prepare for their own locally engineered cotton and soybean varieties to come to market.

Charities, such as the Gates Foundation, are also funding GM crop efforts around the globe. The Rockefeller Foundation, for example, is bankrolling a project to commercialize Golden rice in several Asian countries; this variety, which is engineered to produce beta-carotene, may be a partial solution to vitamin A deficiency in the developing world. Also highly anticipated are the expected debut of drought-tolerant biotech corn in the United States in 2012 and in sub-Saharan Africa in 2017, the ISAAA's James reports.

GM crop production and technology are now central to agriculture in the developing world. This represents an about-face, as most GM crops previously engineered and available on the market were geared towards reducing production costs or the final value of the commodity in areas that already had high productivity levels, like the United States and other industrialized countries, notes the European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO).

In terms of global food production, GM technology must, the EMBO contends, continue to be made available to developing countries where researchers can create or vary crops adapted to local conditions. And GM seeds that are developed locally, or with local or government input and research, “may not arouse quite so much opposition as those from large foreign companies, especially when they provide characteristics that make crops better, not just easier to farm,” points out a February 25, 2010 Economist article on the subject.

The future of GM crops is rife with possibilities – and potential problems. The challenge will be to ensure regulations and regulatory bodies remain in place and continue to be a strong and supported part of the process as we forge ahead into a future full of unforeseen food issues and possible dilemmas.

Read More:

Lead Article: Risk, Regulation, and Reward

Spotlight Article: Biotech Crops Gain Global Foothold

CECHE News: U.S. Food Safety Reform Takes Off

Also Noted: What Risks Do Genetically Engineered Crops Pose to the Environment?

Dr. Sushma Palmer, Program Director

Valeska Stupak, Editor & Design Consultant

Shiraz Mahyera, Systems Manager

Daniel Hollingsworth, Website Consultant