Center for Communications, Health and the Environment

The New Face of Tobacco Control in the United States

America has entered a new phase in the fight against tobacco with the 2009 Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. This landmark legislation grants the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the authority to regulate both current and new tobacco products, and restrict tobacco product marketing.

|

This tobacco-free sports poster featuring Olympic gold medalists Picabo Street (Alpine skiing) Dominique Dawes (gymnastics), Oregon State University football star Ken Simonton, Brazilian soccer star Sisi and World Cup champion mountain biker Alison Dunlap emphasizes that you cannot excel in sports by using tobacco (Source: www.cdc.gov) |

President Obama signed the bill (H.R. 1256/S. 982) into law on June 22, 2009, after the U.S. Congress overwhelmingly approved it by a vote of 79 to 17 in the Senate and 307 to 97 in the House of Representatives. The bill was sponsored by U.S. Reps. Henry Waxman (R-CA) and Todd Platts (R-PA), and the late Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA). It was endorsed by more than 1,000 public health groups, medical societies and other organizations around the country, including the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), American Heart Association, American Lung Association and the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. Recent surveys also found that 70 percent of American voters supported the legislation.

In the works for more than a decade, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act represents the strongest action the federal government has ever taken to reduce tobacco use, the leading preventable cause of death in the United States. Anti-tobacco activists hope that the legislation will end the special protection the U.S. tobacco industry has historically enjoyed and that it will safeguard America’s children, health and longevity by empowering the FDA to take a broad range of unprecedented actions that could significantly reduce the number of people who start using tobacco and considerably increase the number of people who quit using it.

Why This Law Is Needed

Tobacco use kills more than 400,000 Americans annually and results in at least $96 billion in national health care costs and almost $100 billion in lost productivity each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Office on Smoking and Health. Every day, according to experts, 1,200 U.S. lives are lost to tobacco and tobacco-related causes, approximately 3,500 American children try a cigarette for the first time, and more than 1,000 of these children become new, regular daily smokers. One-third of these youth will eventually die prematurely as a result of their addiction.

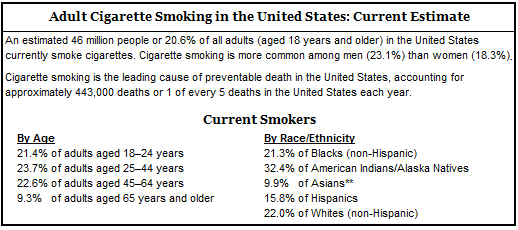

Meanwhile, despite sharp declines in the prevalence of smokers in the United States from 1965 to 2009, almost one in four American men and one in five American women still smoke and are vulnerable to smoking-related death and disease, assert the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and National Center for Health Statistics. Millions of others suffer the effects of secondhand smoke.

Source: CDC. Cigarette Smoking Among Adults and Trends in Smoking Cessation—United States, 2008.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2009;58(44):1227–1232 [accessed 2009 Nov 16].

Even in the face of such staggering statistics and societal costs, “until now, tobacco products have been the most unregulated consumer products on the market,” points out the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids. “They have been exempt from important and basic consumer protections, such as ingredient disclosure, product testing and restrictions on marketing to children.” And they have escaped FDA regulations that apply to other consumer products, including food, drugs, and even lipstick. But no more.

|

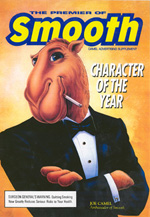

| Under the new U.S. law, advertising supplements like this one will be strictly monitored - and kept out of the hands of minors. |

What the Law Will Do

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act amends the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FFDCA) to grant the FDA authority to regulate the manufacturing, marketing and sale of tobacco products under a new “appropriate for the protection of the public health” standard, as opposed to the “safe and effective” standard currently used for other products under the agency’s purview.

The act establishes the Center for Tobacco Products, a new FDA unit charged with regulating tobacco products and funded by user fees from tobacco manufacturers and importers ($235 million in 2010, rising to $712 million over the next decade). In addition, the law cracks down on tobacco marketing and sales to minors. It requires reinstatement of the 1996 Tobacco Rule, which placed restrictions on tobacco advertising, including a ban on outdoor advertising within 1,000 feet of a school, and was put in place by former FDA Commissioner David Kessler and deemed unconstitutional by the Supreme Court. The reinstated FDA Rule includes new restrictions on tobacco marketing to children and federal prohibition on sales to persons younger than 18 with enhanced enforcement, and will go into effect in mid-2010.

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act also:

- Bans cigarettes having candy, fruit and spice flavors as their characterizing flavors.

- Bans tobacco company sponsorship of sporting events.

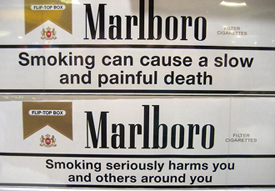

- Requires larger, more effective health warnings on tobacco products.

- Requires tobacco companies to disclose, for the first time ever, the contents of tobacco products, including all ingredients, compounds and additives, as well as changes in products and research about their health effects.

- Requires FDA approval prior to the marketing of any new tobacco product.

- Bans terms such as “light” and “low-tar” that mislead consumers into believing that certain cigarettes are safer.

- Strictly regulates all health-related claims about tobacco products to ensure they are scientifically proven and do not discourage current tobacco users from quitting or encourage new users to start.

- Empowers the FDA to require changes in tobacco products, such as the removal or reduction of harmful ingredients.

- Allows state and local governments to enact, for the first time in almost 40 years, separate tobacco-control measures that may be more rigorous than the FDA directives, including tobacco taxes and restrictions related to the sale, distribution, possession and advertising of tobacco products.

(For a more detailed description of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, go to http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h111-1256&tab=summary. Or to review the act in its entirety, visit http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=111_cong_bills&docid=f:h1256enr.txt.pdf)

How Will the Law Impact the FDA and National Health?

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act could change the face of tobacco control, and the tobacco industry, in the United States. The new law is ambitious, and gives the FDA unprecedented authority to regulate the single most preventable cause of death in the country; it does, however, have limitations. According to Drs. Gregory D. Curfman, Stephen Morrissey and Jeffrey M. Drazen in a September 16, 2008 editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), the act “stops short...of allowing the FDA to ban tobacco products outright or reduce nicotine levels to zero (although it could require that they be lowered).” They also point out that the FDA is not empowered to “set an underage limit of more than 18 years for purchasers of tobacco products, control where they are sold, or make them available by prescription only.” Insignificant, perhaps, when one considers all the other actions the FDA is allowed, and encouraged, to take under the new legislation, but possibly telling.

Legislative limitations aside, the proverbial elephant in the room is the looming question as to how the FDA is actually going to accomplish its new mandate.

The FDA has never had such authority, and responsibility, with regard to tobacco. Historically it has regulated the production and sale of tobacco products in the United States, but the tobacco industry and their products have never fully been under FDA control, as is now the case.

Given that America’s food supply, medicines and other consumer products are under the agency’s purview, the addition of tobacco means that the health of the nation is now firmly in FDA hands, and slave to its regulatory ways and means – procedures and resources that may be insufficient to the task. In short, is the new legislation in keeping with the agency’s public health mission, and will its implementation overload the FDA?

“First, we have concerns that the bill could undermine the public health role of FDA. Second, we have concerns about aspects of the bill that may be extremely difficult for FDA to implement. And third, we have significant concerns about the resources that would be provided under the bill and the expectations it might create,” detailed former FDA Commissioner Andrew C. von Eschenbach in a statement before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Health on October 3, 2007. Von Eschenbach went on to point out the challenge of transforming “existing science into a logical regulatory structure” and lamented the lack of science “on which to base decisions on tobacco product standards...or premarket approval.” He also voiced concern “that the public will believe that products ‘approved’ by the Agency are safe and that this will actually encourage individuals to smoke more rather than less.”

The “most important and daunting challenge,” according to von Eschenbach, however, would be to develop the expertise – and new program – necessary to implement the responsibilities called for in the then-bill, adding that the provisions would require “substantial resources” and that the proposed user fees adjusted for inflation were “not sufficient to implement the complex program” and did not take into account start-up costs. “As a consequence of this,” he cautioned, “FDA may have to divert funds from its other programs, such as addressing the safety of drugs and food, to begin implementing this program.”

Given its current budget, on the food front alone, the FDA was able to review a little over half of the estimated 17.2 million line entries of FDA-regulated imported food products in 2008; and in 2009, it expects that percentage to drop to half. This means that more than 9 million line entries of imported food are entering the United States based on risk assessment, as opposed to physical inspection and field exams. And what about the food produced within U.S. borders?

Samonella outbreaks plagued the country in 2008, with three different strains hitting between spring and the end of the year in products ranging from Minnesota-sourced puffed rice and wheat cereals to Mexican jalapeno peppers to Georgia peanut butter. The bacterium resurfaced on Nebraska alfalfa sprouts in February 2009, followed by a multi-state outbreak of domestically sourced E. coli O157:H7 in prepackaged cookie dough in June, and in beef in July and September.

In most cases, hundreds, and in some cases more than 1,000, people became ill nationwide, with hospitalizations and some deaths. The duration of the peanut butter outbreak alone, which affected more than 500 people, began in September 2008 and continued into April 2009, with the first recall occurring in late January 2009 and the most recent related recall taking place in late March. Identification and containment can take a while, and require significant resources and manpower. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Since 2003, the number of food-borne illness-related outbreaks has increased – representing just one of the FDA’s many pressing mandates.

In fact, the agency appeared overwhelmed, understaffed and under-funded before the tobacco mandate was added – and that was before the current economic crisis. Even as the U.S. government allocates an extra $500 million to the FDA, will this, plus the $230+ million in user fees from the Center for Tobacco Products, be enough to jumpstart and support an overtaxed agency that is already facing a lawsuit jointly filed by several tobacco companies?

It’s too early to tell, but experts note that successful implementation of the landmark legislation could substantially reduce smoking rates and significantly curtail the tobacco-related death toll.

What Effect Will the Law Have on the Tobacco Industry?

Despite questions surrounding the hows of full and effective implementation, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act will undoubtedly affect the tobacco industry. Opinions vary, however, as to the extent of impact.

Not surprisingly, the act was challenged and opposed by several tobacco companies and industry opponents in part because Philip Morris USA (or Altria Group as it has come to be known since the Master Settlement Agreement (MSA)) supported it – and, as the largest tobacco company in the country with the most recognizable products, could weather, effect, and even benefit from, the new restrictions. “There is concern that Philip Morris has taken this unusual action to solidify its dominant position, since the act would make it more difficult to introduce new tobacco products into the U.S. market,” remarked Curfman, Morrissey and Drazen in their September 2008 NEJM editorial.

As early as October 2007, Philip Morris voiced its support for what would eventually become the law, dismissing claims that such legislation would curb competition and pointing out that both new and pre-existing brands increased their market share following the significant restrictions imposed by the MSA.

On June 22, 2009, the day the act was signed into law, Altria Group distributed a press release calling the President’s signing of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act “an important and historic achievement.” It noted that the company “...consistently advocated for federal regulation that recognizes the serious harm caused by tobacco products, that helps ensure tobacco companies do not market tobacco products to children and that also acknowledges that tobacco products are and should remain legal products for adults."

|

Will e-cigs be subject to regulation under the new law? (Source: www.quityoursmokingaddiction.com) |

Two months later, on August 31, 2009, Altria rivals R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. and Lorillard Inc., along with several other tobacco companies, filed suit against federal authorities, claiming that a law (and this law in particular) that gives the FDA new authority over tobacco and that imposes such marketing restrictions violated their right to free speech. Meanwhile, advocates for the electronic cigarette industry were beginning to make their case that “e-cigs,” especially those containing synthetic nicotine or nicotine-like compounds, are not tobacco products and do not fall under the auspices of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. But, as Duane Morris associate Azim Chowdhury points out in the September/October 2009 "Food and Drug Law Institute Update," the act “...contains language that FDA could use to directly regulate and keep smoking alternatives such as e-cigs off the market.... Furthermore, additional overhead and user fees that come with regulation will make it very difficult for small tobacco and e-cig companies to absorb the costs and survive in the market.”

Curfman, Morrissey and Drazen specify concern surrounding the belief that regulation might be “weakened by industry lobbying” since so much of it is unmandated and left to FDA discretion. They also note that “FDA oversight might mitigate the legal liability of tobacco companies.”

In response to the President’s signing of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Kathy Mulvey, international policy director at Corporate Accountability International, questioned Altria/Philip Morris’ support, noting that the tobacco giant “played a central role in challenging FDA regulation of tobacco throughout the 1990s.” She then lamented, “The Act allows for tobacco industry representation on a new scientific advisory committee. Not only is the inclusion of the industry on this committee akin to letting the fox guard the henhouse, it runs counter to a treaty provision that obligates ratifying countries to safeguard their health policies against tobacco industry interference.”

What Does This Law Mean for the Nation, and What Additional Challenges Are in Store as It Is Implemented?

Could the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act actually help Altria/Philip Morris and give the tobacco industry a leg-up?

It’s too early to tell, but Michael Siegel, a physician and professor at Boston University’s School of Public Health, claims in a September 2009 post on tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com that “[The act’s] loopholes – compromises inserted by the public health groups to appease Philip Morris and protect its profits – are so large that they ensure that the law will accomplish nothing.”

|

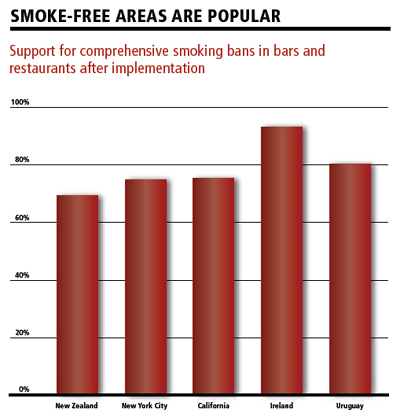

| United States Department of Health and Human Services (2006). Compiled from multiple sources. |

“The long-term impact of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act on the health of the public will depend critically on its implementation through strict regulations, rigorously enforced,” contend Drs. Curfman, Morrissey and Drazen in a July 2009 NEJM editorial. New York City’s 2002 legislation banning smoking in virtually every indoor area, for example, initially sparked intense skepticism and criticism, but ended up gaining widespread acceptance and has been credited with helping to drive down the smoking rate in the city from 21.5 percent in 2002 to 16.9 percent in 2007 – with an outdoor ban affecting city parks, playgrounds, recreational facilities and beaches now in the works.

Much more complex and far-reaching, the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act is just beginning to be implemented, and in the short term, in practice at least, some progress is being made and deadlines met. Reasoning and results, however, appear mixed.

On June 30, 2009, for example, the FDA announced that it was seeking public input on the implementation of the new law, indicating particular interest "…in comments on the approaches and actions the agency should consider initially to increase the likelihood of reducing the incidence and prevalence of tobacco product use and protecting the public health." Interested parties were invited to submit comments by the end of September, at which time, the FDA extended the submission deadline to December 28, 2009, possibly based on a lack of response, as primary supporter ACS CAN didn’t even submit comments until October 2.

Meanwhile, on August 19, 2009, the FDA launched its new Center for Tobacco Products to oversee implementation of the act, appointing as its first director Dr. Lawrence Deyton, an expert on veterans’ health issues, public health and tobacco use, and a clinical professor of medicine and health policy at George Washington University School of Medicine and Health Sciences. In addition, the agency officially established the Tobacco Products Scientific Advisory Committee, lambasted by Mulvey.

On September 22, 2009, fruit- and candy-flavored cigarettes became illegal, ahead of the October 2009 deadline. The next day, Kretek International Inc., the leading importer of clove-flavored cigars, filed suit to prevent the FDA from banning flavored cigars. The very next day, Dr. Siegel noted in a tobaccoanalysis.blogspot.com post that “Philip Morris and R.J. Reynolds confirmed that they have no products on the market which are covered by the cigarette flavoring ban....Instead, the law forced the removal of some minor products made by small manufacturers...and which are hardly smoked by any youths.” He went on to identify “severe loopholes” in the flavoring ban, including the exemption of menthol, which is popular with youth and comprises “about 25% of the market.”

"This is truly a case of an ounce of prevention can prevent a future epidemic," commented Matthew L. Myers, president of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids in a September 2009 online article in U.S. News and World Report on the subject; but the same article reported that flavored cigarettes account for only 1 percent of the cigarette market.

Going forward, according to the FDA Web site:

- By January 2010, tobacco manufacturers and importers will submit information to FDA about ingredients and additives in tobacco products.

- By April 2010, FDA will reissue the 1996 regulation aimed at reducing young people’s access to tobacco products and curbing the appeal of tobacco to the young.

- By July 2010, tobacco manufacturers may no longer use the terms "light," "low" and "mild" on tobacco products without an FDA order in effect.

- By July 2010, warning labels for smokeless tobacco products will be revised and strengthened.

- By October 2012, warning labels for cigarettes will be revised and strengthened.

|

Warning labels like this are coming...but will they do the trick? (Source: www.quityoursmokingaddiction.com) |

It’s a protracted timeline, for sure, but, as former FDA Commissioner von Eschenbach pointed out in his 2007 statement before the U.S. House Subcommittee on Health, “In the best of circumstances when scientific results point to a clear regulatory approach, rulemaking typically involves at least a three-year process. In situations where the science is less fully developed or the issues are complex or controversial, and both are the case here, regulation development requires much more time.”

Ultimately, time will determine the impact and legacy of the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. Time, coupled with commitment, effective enforcement, industry cooperation, and public and political support and advocacy.

There will be controversy, but there will also be conversation and consensus.

The Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act is a step in the right direction. It addresses a looming, and preventable, health issue in a national context, and as a national priority. And like the New York City smoking ban, which became a state-wide mandate in 2003 and was replicated across cities and countries worldwide, this ambitious U.S. law paves the way for global advancement and action.

Read More:

Lead Article: The New Face of Tobacco Control in the United States

CECHE News: Combatting Tobacco and Its Deadly Effects in India

Also Noted: Smoking May Increase Flu Risk

Dr. Sushma Palmer, Program Director

Valeska Stupak, Editor & Design Consultant

Shiraz Mahyera, Systems Manager

Daniel Hollingsworth, Website Consultant